Once upon a time as a 14 year-old I became very depressed. I was told I had depression, a serious illness that I would have to treat by taking antidepressant medications for the rest of my life. I started taking Paxil (a drug since linked to increased suicidality in young people) and it seemed to help me feel better.

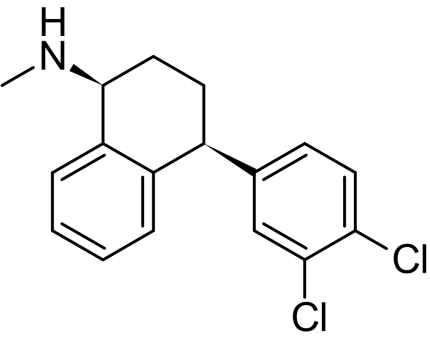

A year later, I wasn’t feeling so well—Paxil’s shine had worn off, and I was depressed again. So the doctor switched me to Zoloft. Aha, relief! But six months later, I wasn’t feeling so well anymore, and they increased the dosage. Then again. And again. Until I arrived at the robust dosage of 250mg a day—that’s a quarter of a gram of mind-altering, liver-assaulting SSRI goodness daily.

I stayed at that dosage for a long, long time. I was not cured—I was still depressed and lived in a doldrums of grey-blue numbness. I also began taking a drug for anxiety—Klonopin, a benzodiazepine. I took that drug for some six years. (Long-term use of benzodiazepines is associated cognitive impairment.)

From the very beginning of my experience with psychiatric treatment I was taught and believed that my sufferings were caused by intrinsic problems with my brain chemistry, and that the solution lay in the ingestion of mind-altering substances. I wondered what past generations had done who had not had access to modern wonder drugs like Zoloft and Klonopin—how had they survived? But I accepted the premise: my brain was the problem, and drugs were the answer.

But drugs were not the answer. Not even close. Each new medication, each new dosage gave me a high and let me forget my problems for a while. But eventually the stimulating effects diminished and I was back where I started, depressed and anxious, living in a tumultuous life with no idea how to make things better.

It’s taken me half my life, but I have come to see depression in a very different light than that showed me by the doctors of my youth. I can sum up this new viewpoint in five simple words:

Depression is not an illness.

I used to see depression as an illness, as a biochemical disorder whose causes and cures had little to do with the agency of the sufferer and everything to do with neurotransmitters. In this paradigm, depression is a random happening, much like cancer or kidney disease may seem. You don’t choose to get depressed, it just comes upon you. It’s beyond your control. That was almost the point.

The idea of depression-as-illness hinges upon a belief that depression originates when serotonin and other neurotransmitters in the brain of the sufferer are “out of balance.” I genuinely believed as a teenager that I suffered a serotonin deficiency that had to be corrected by medication. Yet the science does not bear this up, and in the absence of a clear “chemical imbalance” to correct, the rationale for antidepressants is weakened.

“But,” my informed reader protests, “randomized controlled trials have proven the efficacy of various antidepressant medications, so regardless of whether they correct any imbalances, we know they work.” Good point, Informed Reader—there have indeed been numerous randomized, placebo-controlled experiments that seemingly show the efficacy of the drugs. But the studies in question are, in fact, highly suspect, for a variety of reasons.

First, the vast majority of drug studies in the United States and Europe are funded by the drug companies themselves. In other words, an organization with a vast financial interest in achieving a positive outcome for their drug—“blockbuster” drugs make billions of dollars annually, after all—is financing the study. The researchers they work with are dependent on the drug company for access to medications and data, and thus they are incentivized to provide favorable outcomes as well. The drug companies often retain editorial privileges over the research and can even block the publication of results that they do not approve of.

Thus the published studies are only a sample of all those performed—the “unsuccessful” studies have been omitted from the literature completely. And wealthy drug companies with a huge interest in the outcome are willing and able to perform these studies over and over again until the randomized controlled trial dice come up sixes.

Second, the placebo control in studies of antidepressants is faulty. Antidepressants are known for a number of fairly obvious side-effects, from dry mouth to erectile dysfunction. Inert placebos have no such side-effects, and thus study participants can often discern whether they have been given the drug or the placebo. Studies performed using “active” placebo (a placebo that mimics the side-effects of the drug) greatly narrow the advantage of the drug over the placebo.

There are numerous other reasons the “proof” studies tend to be flawed, anywhere from experimental design to statistical analysis. The point is that apparently, when you dig into the science, very little has actually been proven regarding the “antidepressants” other than that they induce a strong placebo effect and that drug companies will do almost anything to get them approved.

Without a causal mechanism, and without robust evidence that psychoactive medications are any more effective than placebo in treatment of depression, the idea of depression as illness appears suddenly shaky.

If depression is not an illness, then what is it?

I can’t answer that question definitively. Nobody really can. Depression is actually very many things—an emotion, an experience, pain, suffering, personal transformation, spiritual struggle, and so on. Here’s the one that makes most sense to me:

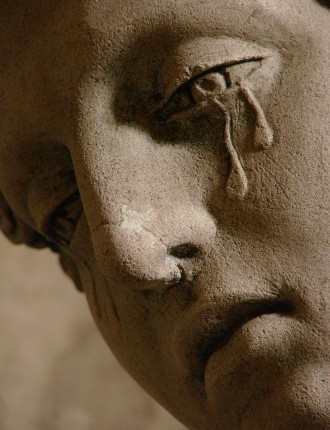

Depression is psychic pain.

I experienced intense physical pain when I broke my collar bone at age 17. The pain made it clear that something was wrong, that I needed to get to a hospital for treatment, and that I should not use my left arm until the bone healed. Physical pain is a vital signal, and we ignore it (or numb it) at our peril. Suppose that upon breaking my collar bone I just took some drugs to make the pain stop and then went back to what I had been doing. I would still have been at risk of shock. By continuing to use my arm, I would have greatly worsened the fracture. Perhaps the next day I would have noticed renewed pain, and taken more painkillers. The bone might have never healed. Nerve damage could have occurred, and who knows what else. All because I ignored my body’s messenger: pain.

For me the same occurred with depression. Depression is psychic or psychological pain, telling us that something is wrong and needs to be fixed. Not a neurochemical imbalance, but something about our emotional and inner life. I grew up in a turbulent family where I had plenty to feel depressed about. Depression was telling me that something was wrong, that there was something that needed to change. But doctors and others, instead of helping me fix the real problems, gave me antidepressants—the painkillers of the mind—to numb my pain. The real issues stayed broken. I was told the drugs were the solution, but though they may have played a helpful role for a moment, drugs were ultimately part of the problem.

I can’t prove that this is the right paradigm, but it makes sense to me. Though I’ve heard objections that there really are people with wonderful lives, loving families, fulfilling careers who feel inexplicably depressed, I stand by the belief that depression is pain telling us something is wrong. The inability of the sufferer to immediately identify the thing that is wrong (like I was unable to as a teenager) does not make it less true. After all, physical pain very often comes in advance of our awareness of its cause—why shouldn’t psychological pain as well?

There are so many things that could be getting people down, from relationships to diet to the inhospitable surroundings of modern urban life, unrealized ambitions, unmourned losses, lack of exercise, lack of love, and whatever else. Maybe there isn’t a chemical imbalance, but there are many other ways our lives can become imbalanced, and I believe depression can help us to notice when this happens and set it right.

Next time you encounter somebody feeling depressed (maybe it’s you), sure, give them some antidepressant “painkillers” for their sorrows if you have to, but don’t leave them with those numbing drugs indefinitely. Help them get to the bottom of the pain. Healing and transformation are so much harder, but so worth it in the end.

Leave a Reply