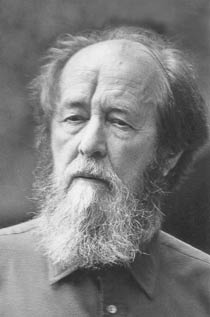

I just learned of the August 3rd 2008 death of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Nobel Prize winner for literature in 1970 and author of the monumental GULAG Archipelago. Many were his critics, East and West, but to me Solzhenitsyn was a hero. A quotation from the New York Times’s obituary sums it up:

Hundreds of well-known intellectuals signed petitions against his silencing; the names of left-leaning figures like Jean-Paul Sartre carried particular weight with Moscow. Other supporters included Graham Greene, Muriel Spark, W. H. Auden, Gunther Grass, Heinrich Boll, Yukio Mishima, Carlos Fuentes and, from the United States, Arthur Miller, John Updike, Truman Capote and Kurt Vonnegut. … That position was confirmed when he was awarded the 1970 Nobel Prize in the face of Moscow’s protests. The Nobel jurists cited him for “the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature.”

Mr. Solzhenitsyn dared not travel to Stockholm to accept the prize for fear that the Soviet authorities would prevent him from returning. But his acceptance address was circulated widely. He recalled a time when “in the midst of exhausting prison camp relocations, marching in a column of prisoners in the gloom of bitterly cold evenings, with strings of camp lights glimmering through the darkness, we would often feel rising in our breast what we would have wanted to shout out to the whole world—if only the whole world could have heard us.”

He wrote that while an ordinary man was obliged “not to participate in lies,” artists had greater responsibilities. “It is within the power of writers and artists to do much more: to defeat the lie!” (Solzhenitsyn, Literary Giant Who Defied Soviets, Dies at 89)

The Discomfort of Truth

From him and his work I learned how radical a thing truth is; how important it is both to be free and to do something worthwhile with freedom; and how to use language—the written and memorized and spoken word—to strike at the heart of evils both overt and subtle. (“Solzhenitzyn’s death reminds us of what writers are supposed to do, which is to speak out in their own voices, even if those voices aren’t comfortable to hear…. He was himself. That is his best epitaph.” Comment by Jane S, California)

Solzhenitsyn was a refreshing throwback to a pre-postmodern world in which the writer used his craft as a documentary of truth, as an agent of social change, as a teacher—not just for entertainment or for “art for art’s sake,” worthy as those ends are. You know, back when art was allowed to mean things. The conscientious writer, according to Solzhenitsyn, had to create socially responsible acts of literature, works that called things as they were and challenged an entire people to discern their own faults and rise above them. As a BBC article stated, “Solzhenitsyn [stood] in a thoroughly Russian tradition, which imposes upon the writer a duty not simply to write well, but to voice the pains and aspirations of his society. This civic obligation [was] one Solzhenitsyn felt acutely, and the post-Modernist relativism of the late 20th Century [was] alien to him.” (Solzhenitsyn: A tortured patriot)

Solzhenitsyn acknowledged the writer’s responsibility to tell truth. Yet, he did not have a strictly ideological view of truth or right. Rather, it was highly nuanced, as the works of his predecessors (Doestoyevsky and Tolstoy) would have us understand. The same article from the BBC reported:

For Solzhenitsyn, right and wrong, good and evil, undoubtedly do exist. However, as he first expressed it in a poem written in his head in the camps nearly 60 years ago, the dividing line between good and evil passes not between warring parties, ideologies, armies, but runs through the heart of each individual and flickers ceaselessly to and fro. (Solzhenitsyn: A tortured patriot)

The GULAG

When you see Lenin, Aleksandr, please punch him in the mouth.—Richard Collins, NYC (Comment by Richard Collins, NYC)

I heartily recommend The GULAG Archipelago. Its documentation of Soviet insanity in connection with the GULAG prison camp system—and of the will of those who survived (or succumbed to) it—will increase your appreciation for life and freedom. I wrote about dark things as a subject of media in a recent post. Well, this is dark. Very dark. And cynical towards those who perpetrate evil. Oh, perhaps the Russians weren’t systematically executing their prisoners in quite the same way the Germans did. But millions died nonetheless.

GULAG Archipelago, as well as Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, not only let the reader begin to feel the despair of millions imprisoned for minor criticism of the government or for their religion of for owning property, but also the grinding hopelessness of the vast Soviet empire being slowly smothered, crushed, by its own brutal Communist yoke. You will never get out alive. If you don’t steal your neighbor’s bread you’ll be dead in a week, but you just watched your campmates carry out a vigilante-style execution against a prisoner who did just that. If you escape the walls of the camp, you have to survive undetected a thousand kilometers of barren steppe in every direction. KGB is never far behind.

Prophecy

In the more “prophetic” vein of Solzhenitsyn’s work, I highly suggest his commencement address at Harvard University in 1978. (A World Split Apart) He derides Western material and consumer culture in no uncertain terms (“And he once likened American culture to ‘manure.’ Atta boy, Al! He was nobody’s pawn.” Comment by Phil, Colorado), unwilling to accommodate such profligate living on the part of the “good guys”. It wasn’t good enough simply to be the un-Communism. He told us to be something more. (“A prophet without honor in his own country. Blew the lid off soviet fascism for eternity. Single minded, difficult, brilliant, deeply spiritual, a true force of nature, and outside of Mandela, the only Shakespearean character left on the world stage. Go to your rest, Alexandr. Go in peace.” Comment by Patrick, Brooklyn. Of course, “soviet fascism” seems a bit of a contradiction of terms. Oh well.)

One final comment taken from the New York Times article sums up my feelings perfectly:

I and millions have lost a great friend, but he will live forever in his books—Cancer Ward, the First Circle, A Day in the Life, all of the Gulag. He has immeasurably enriched countless lives. (Comment by Michael Lydon)

A great friend indeed.

Leave a Reply